Post by TasunkaWitko on Sept 4, 2015 16:54:34 GMT -5

Tandoori Murg

Roast Chicken With Yoghurt Masala

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969):

This dish, with only slightly-different variations, is universal throughout India and Pakistan, a region that I refer to as South Asia. I am making an adapted version of this right now, using chicken thighs that I will grill on my Weber Kettle tomorrow.

The chapter discussing grilled and barbecued foods in the Indian volume of Time/Life’s Foods of the World series provides a few slight differences when compared to the recipe above. In the chapter, the chickens are skinned and limes are used instead of lemons. These changes sounded sensible to me, and dovetailed with what little I know about the cuisine, so I did the same. On the flip-side of that, I was forced to take a couple of shortcuts, due to availability of ingredients and other factors. These adaptations will be enumerated below.

I began by starting 1 teaspoon of saffron steeping in 3 tablespoons of very hot water:

As is always the case with saffron, the characteristics were simply incredible - a deep, rich, golden hue paired with an earthy, slightly-floral fragrance, carrying the promise of exotic Eastern flavours. This description hardly does justice to this most special of ingredients, and in my opinion saffron is worth every penny that it costs.

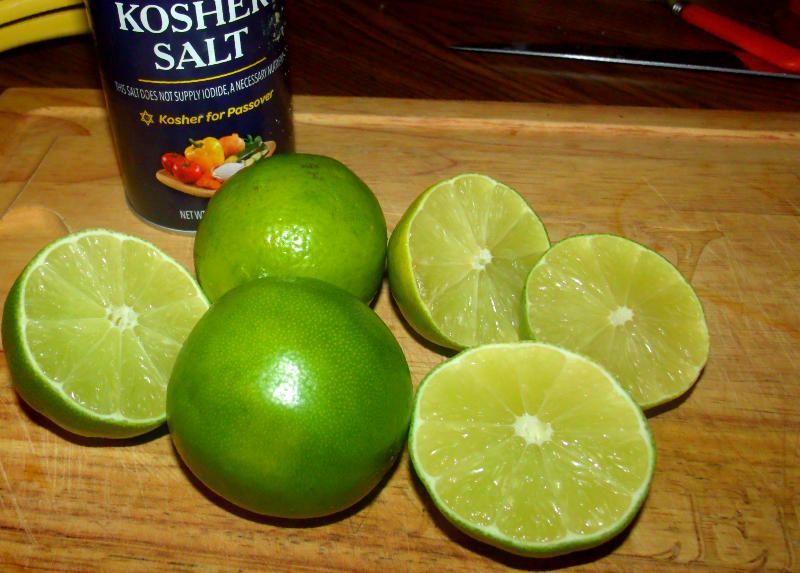

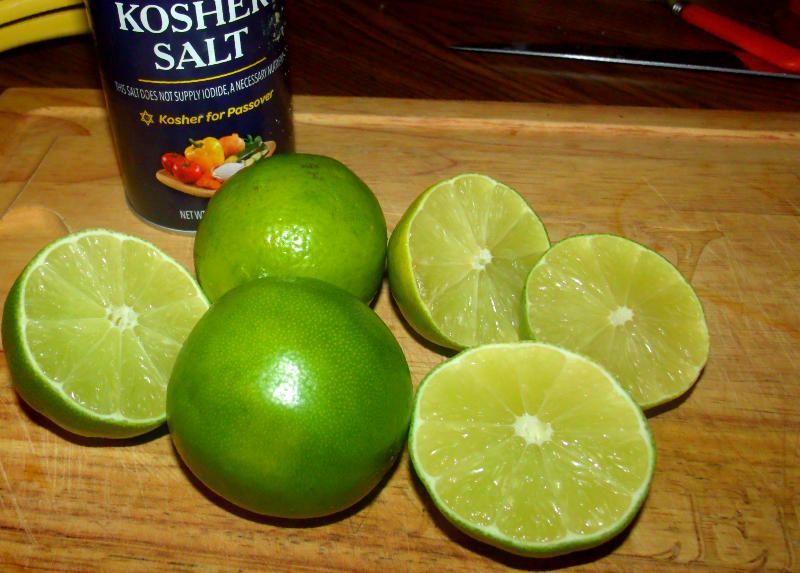

As the saffron steeped, I collected 1/2 cup of freshly-squeezed lime juice:

As it turned out, I only needed three limes to get the needed amount, rather than four.

The recipe above calls for lemons, and that is perfectly acceptable; however, the chapter preceding the recipe mentioned limes, which are also true to the cuisine, so I used them in order to see how they would work.

Once the lime juice was collected, I prepared my boneless, skinless chicken thighs by slashing each of them twice:

The idea here, of course, is to get the flavour of the spices and other ingredients into the chicken.

Next, I combined the lime juice, salt and saffron (along with the steeping water) with the chicken in a large, Zip-Lock-style bag:

I worked the marinade into the chicken thoroughly, then let the chicken soak it in for 30 minutes, flipping the bag once after 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, I assembled my spices and other ingredients:

Clockwise from the top: 2 teaspoons of coriander, 1 teaspoon of cumin, about 1.5 tablespoons of ginger paste, 2 teaspoons of garlic paste and about 1.5 teaspoons of commercial chili powder.

Because I had no cumin and coriander seeds available to me, I was forced to use good-quality ground versions of those spices; however, I am sure that all will be fine in the end. Also, for the sake of The Beautiful Mrs. Tas, I substituted good-quality chili powder instead of cayenne. I know it is illogical, but she can abide chili powder just fine, whereas even 1/8 of a teaspoon of cayenne (or worse, ground "real" Indian chiles) will have her feeling like she needs to be hospitalized. I have observed this through experimentation over the years and somehow she always knows - and suffers - if I use anything other than chili powder, so I simply use chili powder - happy wife, happy life. Finally, I decided - mostly for the sake of experimentation, to use ginger paste and garlic paste, rather than fresh ginger and garlic. I did this to see how these ingredients would work in a dish such as this, and also because I am skeptical of the “fresh” ginger that is available locally, especially after seeing how “fresh” the “fresh” coconuts and pineapples are.

Moving along, I also measured out 1 cup of Greek yoghurt:

The yoghurt, as far as I can tell, aids in the marinating of the meat, and also serves to mellow out the heat that is quintessential to Indian and Pakistani cuisine.

When the chicken was finished marinating in the lime juice/salt/saffron mixture, I stirred the spices, ginger and garlic into the yoghurt:

The aromas coming from this combination were incredible, and I suspected that I was in for some wonderful things. I snuck a little taste of the yoghurt masala, and was truly impressed with my first real experience in Indian cuisine.

The recipe calls for the use of a 1/2 teaspoon of red food colouring in the masala, to provide a traditional crimson hue. This colouring is mentioned in many, many recipes for this and similar dishes, and appears to be perfectly acceptable; however, some choose not to use if for various reasons. I went back and forth over whether to use this while I was shopping for ingredients, but eventually decided not to; it was just as well, since when I got home I discovered that we didn’t have any red food colouring anyway.

Ready to proceed, I added the yoghurt masala to the chicken in the bag, taking care to distribute it evenly and mix it in thoroughly:

And that’s all there is to it, so far. The chicken is currently marinating in the refrigerator until tomorrow, at which time I will grill it over charcoal in my Weber Kettle, perhaps adding a little apple or pecan for a bit of smoky goodness. The kettle - as I will use it - will make a good substitute for the traditional tandoori ovens that are used in India and Pakistan. Part of the actual cooking of the chicken involves the use of ghee, which is a rich, nutty-tasting South-Asian version of clarified butter that is very easy to produce at home and has dozens of uses. I made a batch of ghee earlier today, so I am ready to go with that.

It is my intention to serve the finished chicken with a traditional indian salad and perhaps some home-baked naan bread, if I can get it made.

More to come as it happens, etc. &c....

(later)

Many Indian dishes are served with salat, often with the main course piled on top of it as part of the presentation. It is extremely easy to make and lends itself well to improvisation; if you don’t like or are missing a particular ingredient at the moment, you can certainly substitute with something else, for the most part.

Here is the recipe for the salat that I made to go with the chicken:

Let's give this a go!

Here are the ingredients that I used to make my salat:

A few notes:

The recipe called for two large onions, but my onions weren’t that big, so I used three. Two would have been just about right, I think.

I used three tomatoes, rather than two, simply because we had three in the house that needed to be used, and also because I really like tomatoes.

I used half the radishes called for, because I’ve never really been a fan of them. As it turns out, they were actually very good in this preparation, but I still think that half was the best amount to use.

The commentary in the chapter mentions limes, but the recipe section calls for lemons; I decided to use both of these citrus fruits. My reasons were for the colour contrast in presentation and because I like the way that lemon and lime juice go together.

I didn’t have any “fresh hot green chilies,” and The Beautiful Mrs. Tas wouldn’t have let me use them anyway; however, the commentary mentioned that sometimes pickled vegetables are used in salat, and these pepperoncinis seemed like a great idea.

Following the pickling concept described above, and remembering that the commentary mentioned cucumbers as a common accompaniment, I also decided to go with slices of “zesty” dill pickles, because they are packed with flavour, including a bit of “hot’ red pepper in the brine.

Anyway, if you haven’t guessed by now, this salat is indeed versatile; hopefully, the recipe list and my twists on it will demonstrate the necessary “basics” of it, as well as the possibilities.

To get started, I peeled and sliced the onions as thinly as I could with the knife I had, then spread them out evenly on a platter:

The recipe advises to slice them lengthwise (with the “grain”), but for some illogical reason, I have never been able to stand onions that are sliced that way, so I cut them crosswise (against the “grain”). I doubt that there is a huge difference, either way.

I was rather skeptical about the amount of onions - and as it turns out, I probably was slightly over-loaded with them. Having said that, this worked well, so do not be afraid to trust the recipe where the onions are concerned.

Once the onions were finished, I sliced the tomatoes and arranged them in a ring near the outer edge of the platter:

Between each major “layer” of the salat, I sprinkled a bit of salt with a few short grindings of black pepper.

I like tomatoes, and in my opinion, I could have put a whole layer of sliced tomatoes over the onions and it would have been great!

Next came the radishes:

As you can see, I sliced them thinly with a mandolin, both because I really don’t like whole radishes and because I thought they would look nice. Considering the really nice colour combinations I was beginning to get, I am sure that I am not the first person to do this when making an Indian-style salat. The effect was simply too nice, in my opinion, not to have been done before.

After the radishes, I cut the lemons and limes into wedges and arranged them around the platter:

This made a really nice visual impact, and I am glad that I chose to use both fruits; however, one or the other would be just as nice.

Next, the slices of pickles:

Slightly-departed from the recipe, but still within the spirit of the cuisine, I hope.

After the slices of pickles, I placed the pepperoncinis:

Once again, I am sure that I am not the first to have done something similar.

After that, I drizzled the salat with a freshly-squeezed combination of lemon and lime juices. I ended up having close to a half-cup, which is twice what the recipe calls for, but it was all good.

And that’s pretty much it! Here is a photo of the finished salat:

As mentioned above, salat is a traditional accompaniment to many Indian meals, especially those cooked over a fire. I was expecting this colourful dish to be pretty good, in spite of my modifications, but was surprised at just how delicious it was. The crisp, raw vegetables all worked very well together, accented by the bright citrus juice, which had the effect of “pickling” the onions and radishes a bit and toning down the harsh bite that I was expecting. I was also pleased with how well it looked from a visual standpoint; the colours are incredible, and really are part of the enjoyment of the dish, in my opinion.

Altogether, I was very happy with this side dish and expect to use it many more times, especially when cooking South-Asian cuisine.

(later)

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969):

Reading the above passage, I was impressed with the influx of knowledge, technique and (using the author’s word) nostalgia that came through the pages, reaching out to me, nearly 50 years later (and by way of her memories, more than 20 years before that), and inspiring me to try this dish. Her descriptions of these meals - not just the food itself, but the time, place, methods and ingredients - paint a picture of Punjabi life that cannot easily be forgotten. My available ingredients and resources necessitated some very slight variations from the author’s description, but I do not feel that the experience was deprived or diminished in the slightest - this was a flat-out wonderful meal, and one that i intend to enjoy many times in the future.

When the time came to actually cook the chicken, I removed the pieces from the masala marinade and laid them out on a tray, brushing each thigh with a splash of ghee:

It was looking great, and it smelling even better! The aromatic mix of spices was an exotic feast in itself; I truly believe that the saffron makes the dish here, in the way that it creates beautiful harmonies with some aromas while bringing other subtle aromas closer to the front. The citrus juices also contribute to a sunny, refreshing ambience that plays an exquisite counter to the earthy spices. The resulting melange is much more than the sum of its parts.

By this time, my Weber Kettle was good and hot, so I laid the chicken out on the grate, positioning it around the central Vortex:

The idea here is that the Vortex concentrates the heat, sending it out to circulate for intense, even heating. It worked very well in my opinion, but please note that your charcoal grill, gas grill or even your oven at high heat will work as well. The Vortex helps you get a little closer to how it's done in India, but there are many ways to skin a cat...or cook a chicken!

Because I elected not to use the red food colouring, the chicken took on a wonderful, roasty-golden brown as it cooked:

One key point is to baste the surface of the chicken pieces now and then with the leftover masala marinade, for flavor, colour and a nice, slightly-crisp exterior. Not too much, but just enough. I also dashed a little bit of ghee onto the chicken during cooking, as well.

By the time they were done, the chicken thighs all looked like wonderful pockets of Punjabi heaven:

What do you think?

Just looking at these photos, I know that I already want to make this again!

In the Punjabi tradition, I served the chicken piled on top of the gorgeous salat:

This created what I consider to be a wonderful feast for the eyes as well as the nose, with the promise of absolute paradise for the palate:

When plating the meal, I tried to keep the parade of colours on exhibition, while also keeping things simple; a simple dusting of garam masala and an opportunity for a splash of lemon and lime was really all that was needed:

This meal was light and - as far as I can determine - quite healthy; it was also very delicious, with the tender, marinated chicken soaking up the earthy spices and bright citrus and ginger highlights. Just as the commentary above describes, the flavours are found throughout the chicken, and not simple concentrated on the surface. It really was unlike anything I have ever had before; but at the same time, it tasted pretty much the way I expected it to - only better!

This recipe, like most from the region, is intended to be just a bit spicier, using hotter peppers; the yogurt or curd in the marinade will tone these down a bit, but for those who are sensitive to hot, spicy foods, my chili powder substitutions as outlined above worked very well, bringing the dish into great balance. Everything worked together - the fabulous chicken with its incredible mix of spices, the crisp, raw vegetables and the piquant pickled foods with the citrus dressing - an amazing symphony that belied the simplicity of the ingredients and the preparation. This was truly one of those meals that gives incredible bang for the buck:

My only regret, and this is 100% my fault, is that this meal screams for a flatbread - any flatbread - and I had none. Even a heated flour tortilla, spread with some ghee, would have been good, allowing the chicken and salat to be wrapped with warm, loving goodness and held in the hand as it was eaten. Due to time constraints, I wasn’t able to make a flatbread for this meal, but I will be sure to do so next time.

I hope that my demonstration of this traditional Punjabi meal will inspire you to try these incredible recipes; they are not the least bit complicated and can be prepared very easily on your grill at home, or in the oven, if need be. You will not be disappointed, and just might find a new favourite.

As always, if there are any questions, please be sure to ask them, and feedback is always welcome. Thank you for taking the time to read this, and if do you do try it, enjoy!

Ron

Roast Chicken With Yoghurt Masala

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969):

To serve 6 to 8:

1 teaspoon saffron threads

3 tablespoons boiling water

2 chickens, 2.5 to 3 pounds each

1/2 cup fresh lemon juice

4 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

A 1-inch piece of fresh ginger root, scraped and coarsely chopped

2 medium-sized garlic cloves, coarsely chopped

1 cup unflavored yoghurt

1/2 teaspoon red food coloring

1/4 teaspoon ground hot red pepper

2 tablespoons ghee

Drop the saffron threads into a small bowl or cup, pour in the boiling water, and soak for 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, pat the chickens completely dry inside and out with paper towels and truss the birds securely. With a small, sharp knife cut 2 slits about 1/2-inch deep and 1 inch long in both thighs and breasts of each bird. Mix the lemon juice with the salt and rub them over the chickens, pressing the mixture deeply into the slits. Place the chickens in a large, deep casserole, pour the saffron and its soaking water over them, and let them marinate at room temperature for about 30 minutes.

Sprinkle the coriander and cumin seeds into a small ungreased skillet and, shaking the pan constantly, toast them over moderate heat for a minute or so. Then drop the seeds into the jar of an electric blender, add the ginger, garlic and 2 tablespoons of the yoghurt, and blend at high speed until the mixture is reduced to a smooth paste. With a rubber spatula, scrape the paste into a mixing bowl. Stir in all of the remaining yoghurt, the food coloring and the hot red pepper.

Spread the yoghurt masala evenly over the chickens, cover the casserole with a lid or foil, and marinate for 12 hours or overnight at room temperature, or for at least 24 hours in the refrigerator.

Preheat the oven to 400°F. Arrange the chickens side by side on a rack in a shallow roasting pan large enough to hold them comfortably. Pour any liquid that has accumulated in the casserole over the chickens and coat each one with 1 tablespoon of the ghee. Roast uncovered in the middle of the oven for 15 minutes, then reduce the heat to 350°F, and continue roasting the birds undisturbed for 1 hour more. To test each chicken for doneness, pierce the thigh with the point of a small, sharp knife. The juice that runs out should be pale yellow; if it is still tinged with pink, roast the chicken for another 5 to 10 minutes.

Remove the birds from the oven, cut away the trussing strings, and let the chickens rest for 5 minutes or so for easier carving. Just before serving, cut each chicken into 6 or 8 serving pieces and arrange them attractively on top of a platter of salat or place the whole birds in the center of a large heated platter and garnish the rim with the salat ingredients.

Outdoor Cooking:

In India, tandoori murg is roasted in a special clay oven over hot coals. You can get a somewhat similar smoky flavor by roasting the birds in a hooded charcoal grill equipped with a rotating spit.

Following the recipe above, prepare and marinate the chickens without trussing them. About 2 hours before you plan to serve the tandoori murg, light a 1- to 2-inch-thick layer of coals in the grill, cover it with the hood, and let the charcoal burn until white ash appears on the surface. This may take as long as an hour.

One at a time, remove the chickens from the marinade and string them lengthwise end to end on the spit. (The birds will be wet and slippery, so it is a good idea to do this in the kitchen over a counter or table.) Anchor the chickens in place on the spit with the sliding prongs. Then tie the drumsticks and wings snugly against the bodies of the birds with short lengths of wire, twisting the ends of the wire tightly to hold them securely.

Fit the spit into place above the coals and plug it in. Baste the chickens with the ghee, cover the grill with the hood, and roast for about 1 hour. Baste the roasting birds 3 or 4 times with a tablespoon or so of the remaining marinade, but do not use the liquid lavishly; it may cause the coals to flame up and burn the chickens. To test for doneness, pierce a thigh with the point of a small knife; the juice that runs out should be pale yellow.

To serve, remove the spit from the grill, unscrew the prongs, and slide the chickens onto a platter. Untwist or cut off the wires. Cut the birds into pieces and serve them on top of a platter of salat, or place the chickens in the center of a large platter and garnish the rim with the salat ingredients.

1 teaspoon saffron threads

3 tablespoons boiling water

2 chickens, 2.5 to 3 pounds each

1/2 cup fresh lemon juice

4 teaspoons salt

2 teaspoons coriander seeds

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

A 1-inch piece of fresh ginger root, scraped and coarsely chopped

2 medium-sized garlic cloves, coarsely chopped

1 cup unflavored yoghurt

1/2 teaspoon red food coloring

1/4 teaspoon ground hot red pepper

2 tablespoons ghee

Drop the saffron threads into a small bowl or cup, pour in the boiling water, and soak for 5 minutes.

Meanwhile, pat the chickens completely dry inside and out with paper towels and truss the birds securely. With a small, sharp knife cut 2 slits about 1/2-inch deep and 1 inch long in both thighs and breasts of each bird. Mix the lemon juice with the salt and rub them over the chickens, pressing the mixture deeply into the slits. Place the chickens in a large, deep casserole, pour the saffron and its soaking water over them, and let them marinate at room temperature for about 30 minutes.

Sprinkle the coriander and cumin seeds into a small ungreased skillet and, shaking the pan constantly, toast them over moderate heat for a minute or so. Then drop the seeds into the jar of an electric blender, add the ginger, garlic and 2 tablespoons of the yoghurt, and blend at high speed until the mixture is reduced to a smooth paste. With a rubber spatula, scrape the paste into a mixing bowl. Stir in all of the remaining yoghurt, the food coloring and the hot red pepper.

Spread the yoghurt masala evenly over the chickens, cover the casserole with a lid or foil, and marinate for 12 hours or overnight at room temperature, or for at least 24 hours in the refrigerator.

Preheat the oven to 400°F. Arrange the chickens side by side on a rack in a shallow roasting pan large enough to hold them comfortably. Pour any liquid that has accumulated in the casserole over the chickens and coat each one with 1 tablespoon of the ghee. Roast uncovered in the middle of the oven for 15 minutes, then reduce the heat to 350°F, and continue roasting the birds undisturbed for 1 hour more. To test each chicken for doneness, pierce the thigh with the point of a small, sharp knife. The juice that runs out should be pale yellow; if it is still tinged with pink, roast the chicken for another 5 to 10 minutes.

Remove the birds from the oven, cut away the trussing strings, and let the chickens rest for 5 minutes or so for easier carving. Just before serving, cut each chicken into 6 or 8 serving pieces and arrange them attractively on top of a platter of salat or place the whole birds in the center of a large heated platter and garnish the rim with the salat ingredients.

Outdoor Cooking:

In India, tandoori murg is roasted in a special clay oven over hot coals. You can get a somewhat similar smoky flavor by roasting the birds in a hooded charcoal grill equipped with a rotating spit.

Following the recipe above, prepare and marinate the chickens without trussing them. About 2 hours before you plan to serve the tandoori murg, light a 1- to 2-inch-thick layer of coals in the grill, cover it with the hood, and let the charcoal burn until white ash appears on the surface. This may take as long as an hour.

One at a time, remove the chickens from the marinade and string them lengthwise end to end on the spit. (The birds will be wet and slippery, so it is a good idea to do this in the kitchen over a counter or table.) Anchor the chickens in place on the spit with the sliding prongs. Then tie the drumsticks and wings snugly against the bodies of the birds with short lengths of wire, twisting the ends of the wire tightly to hold them securely.

Fit the spit into place above the coals and plug it in. Baste the chickens with the ghee, cover the grill with the hood, and roast for about 1 hour. Baste the roasting birds 3 or 4 times with a tablespoon or so of the remaining marinade, but do not use the liquid lavishly; it may cause the coals to flame up and burn the chickens. To test for doneness, pierce a thigh with the point of a small knife; the juice that runs out should be pale yellow.

To serve, remove the spit from the grill, unscrew the prongs, and slide the chickens onto a platter. Untwist or cut off the wires. Cut the birds into pieces and serve them on top of a platter of salat, or place the chickens in the center of a large platter and garnish the rim with the salat ingredients.

This dish, with only slightly-different variations, is universal throughout India and Pakistan, a region that I refer to as South Asia. I am making an adapted version of this right now, using chicken thighs that I will grill on my Weber Kettle tomorrow.

The chapter discussing grilled and barbecued foods in the Indian volume of Time/Life’s Foods of the World series provides a few slight differences when compared to the recipe above. In the chapter, the chickens are skinned and limes are used instead of lemons. These changes sounded sensible to me, and dovetailed with what little I know about the cuisine, so I did the same. On the flip-side of that, I was forced to take a couple of shortcuts, due to availability of ingredients and other factors. These adaptations will be enumerated below.

I began by starting 1 teaspoon of saffron steeping in 3 tablespoons of very hot water:

As is always the case with saffron, the characteristics were simply incredible - a deep, rich, golden hue paired with an earthy, slightly-floral fragrance, carrying the promise of exotic Eastern flavours. This description hardly does justice to this most special of ingredients, and in my opinion saffron is worth every penny that it costs.

As the saffron steeped, I collected 1/2 cup of freshly-squeezed lime juice:

As it turned out, I only needed three limes to get the needed amount, rather than four.

The recipe above calls for lemons, and that is perfectly acceptable; however, the chapter preceding the recipe mentioned limes, which are also true to the cuisine, so I used them in order to see how they would work.

Once the lime juice was collected, I prepared my boneless, skinless chicken thighs by slashing each of them twice:

The idea here, of course, is to get the flavour of the spices and other ingredients into the chicken.

Next, I combined the lime juice, salt and saffron (along with the steeping water) with the chicken in a large, Zip-Lock-style bag:

I worked the marinade into the chicken thoroughly, then let the chicken soak it in for 30 minutes, flipping the bag once after 15 minutes.

Meanwhile, I assembled my spices and other ingredients:

Clockwise from the top: 2 teaspoons of coriander, 1 teaspoon of cumin, about 1.5 tablespoons of ginger paste, 2 teaspoons of garlic paste and about 1.5 teaspoons of commercial chili powder.

Because I had no cumin and coriander seeds available to me, I was forced to use good-quality ground versions of those spices; however, I am sure that all will be fine in the end. Also, for the sake of The Beautiful Mrs. Tas, I substituted good-quality chili powder instead of cayenne. I know it is illogical, but she can abide chili powder just fine, whereas even 1/8 of a teaspoon of cayenne (or worse, ground "real" Indian chiles) will have her feeling like she needs to be hospitalized. I have observed this through experimentation over the years and somehow she always knows - and suffers - if I use anything other than chili powder, so I simply use chili powder - happy wife, happy life. Finally, I decided - mostly for the sake of experimentation, to use ginger paste and garlic paste, rather than fresh ginger and garlic. I did this to see how these ingredients would work in a dish such as this, and also because I am skeptical of the “fresh” ginger that is available locally, especially after seeing how “fresh” the “fresh” coconuts and pineapples are.

Moving along, I also measured out 1 cup of Greek yoghurt:

The yoghurt, as far as I can tell, aids in the marinating of the meat, and also serves to mellow out the heat that is quintessential to Indian and Pakistani cuisine.

When the chicken was finished marinating in the lime juice/salt/saffron mixture, I stirred the spices, ginger and garlic into the yoghurt:

The aromas coming from this combination were incredible, and I suspected that I was in for some wonderful things. I snuck a little taste of the yoghurt masala, and was truly impressed with my first real experience in Indian cuisine.

The recipe calls for the use of a 1/2 teaspoon of red food colouring in the masala, to provide a traditional crimson hue. This colouring is mentioned in many, many recipes for this and similar dishes, and appears to be perfectly acceptable; however, some choose not to use if for various reasons. I went back and forth over whether to use this while I was shopping for ingredients, but eventually decided not to; it was just as well, since when I got home I discovered that we didn’t have any red food colouring anyway.

Ready to proceed, I added the yoghurt masala to the chicken in the bag, taking care to distribute it evenly and mix it in thoroughly:

And that’s all there is to it, so far. The chicken is currently marinating in the refrigerator until tomorrow, at which time I will grill it over charcoal in my Weber Kettle, perhaps adding a little apple or pecan for a bit of smoky goodness. The kettle - as I will use it - will make a good substitute for the traditional tandoori ovens that are used in India and Pakistan. Part of the actual cooking of the chicken involves the use of ghee, which is a rich, nutty-tasting South-Asian version of clarified butter that is very easy to produce at home and has dozens of uses. I made a batch of ghee earlier today, so I am ready to go with that.

It is my intention to serve the finished chicken with a traditional indian salad and perhaps some home-baked naan bread, if I can get it made.

More to come as it happens, etc. &c....

(later)

Many Indian dishes are served with salat, often with the main course piled on top of it as part of the presentation. It is extremely easy to make and lends itself well to improvisation; if you don’t like or are missing a particular ingredient at the moment, you can certainly substitute with something else, for the most part.

Here is the recipe for the salat that I made to go with the chicken:

Salat

Mixed Vegetable Salad

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969)

To serve 4 to 6:

2 large onions, peeled, cut in half lengthwise, then cut lengthwise into paper-thin slivers

2 large firm, ripe tomatoes, washed, stemmed and cut crosswise into 1/4-inch-thick slices

24 radishes, trimmed and washed

2 medium-sized lemons, each cut lengthwise into quarters

3 fresh hot green chilies, each about 3 inches long, washed, slit in half lengthwise and seeded

1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

1 teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Spread the slivers of onion evenly over the entire surface of a large serving platter and arrange the tomato slices in a ring around the edge. Arrange the radishes, lemon wedges and chilies decoratively around the tomatoes, and sprinkle the vegetables evenly with the lemon juice, salt and a liberal grinding of black pepper.

Salat is a traditional accompaniment to such tandoori meats as tandoori murg, husaini kabab or moghlai kabab. After the meat is cooked, it is placed on top of the salat and is usually sprinkled with a little garam masala before serving.

Mixed Vegetable Salad

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969)

To serve 4 to 6:

2 large onions, peeled, cut in half lengthwise, then cut lengthwise into paper-thin slivers

2 large firm, ripe tomatoes, washed, stemmed and cut crosswise into 1/4-inch-thick slices

24 radishes, trimmed and washed

2 medium-sized lemons, each cut lengthwise into quarters

3 fresh hot green chilies, each about 3 inches long, washed, slit in half lengthwise and seeded

1/4 cup fresh lemon juice

1 teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Spread the slivers of onion evenly over the entire surface of a large serving platter and arrange the tomato slices in a ring around the edge. Arrange the radishes, lemon wedges and chilies decoratively around the tomatoes, and sprinkle the vegetables evenly with the lemon juice, salt and a liberal grinding of black pepper.

Salat is a traditional accompaniment to such tandoori meats as tandoori murg, husaini kabab or moghlai kabab. After the meat is cooked, it is placed on top of the salat and is usually sprinkled with a little garam masala before serving.

Let's give this a go!

Here are the ingredients that I used to make my salat:

A few notes:

The recipe called for two large onions, but my onions weren’t that big, so I used three. Two would have been just about right, I think.

I used three tomatoes, rather than two, simply because we had three in the house that needed to be used, and also because I really like tomatoes.

I used half the radishes called for, because I’ve never really been a fan of them. As it turns out, they were actually very good in this preparation, but I still think that half was the best amount to use.

The commentary in the chapter mentions limes, but the recipe section calls for lemons; I decided to use both of these citrus fruits. My reasons were for the colour contrast in presentation and because I like the way that lemon and lime juice go together.

I didn’t have any “fresh hot green chilies,” and The Beautiful Mrs. Tas wouldn’t have let me use them anyway; however, the commentary mentioned that sometimes pickled vegetables are used in salat, and these pepperoncinis seemed like a great idea.

Following the pickling concept described above, and remembering that the commentary mentioned cucumbers as a common accompaniment, I also decided to go with slices of “zesty” dill pickles, because they are packed with flavour, including a bit of “hot’ red pepper in the brine.

Anyway, if you haven’t guessed by now, this salat is indeed versatile; hopefully, the recipe list and my twists on it will demonstrate the necessary “basics” of it, as well as the possibilities.

To get started, I peeled and sliced the onions as thinly as I could with the knife I had, then spread them out evenly on a platter:

The recipe advises to slice them lengthwise (with the “grain”), but for some illogical reason, I have never been able to stand onions that are sliced that way, so I cut them crosswise (against the “grain”). I doubt that there is a huge difference, either way.

I was rather skeptical about the amount of onions - and as it turns out, I probably was slightly over-loaded with them. Having said that, this worked well, so do not be afraid to trust the recipe where the onions are concerned.

Once the onions were finished, I sliced the tomatoes and arranged them in a ring near the outer edge of the platter:

Between each major “layer” of the salat, I sprinkled a bit of salt with a few short grindings of black pepper.

I like tomatoes, and in my opinion, I could have put a whole layer of sliced tomatoes over the onions and it would have been great!

Next came the radishes:

As you can see, I sliced them thinly with a mandolin, both because I really don’t like whole radishes and because I thought they would look nice. Considering the really nice colour combinations I was beginning to get, I am sure that I am not the first person to do this when making an Indian-style salat. The effect was simply too nice, in my opinion, not to have been done before.

After the radishes, I cut the lemons and limes into wedges and arranged them around the platter:

This made a really nice visual impact, and I am glad that I chose to use both fruits; however, one or the other would be just as nice.

Next, the slices of pickles:

Slightly-departed from the recipe, but still within the spirit of the cuisine, I hope.

After the slices of pickles, I placed the pepperoncinis:

Once again, I am sure that I am not the first to have done something similar.

After that, I drizzled the salat with a freshly-squeezed combination of lemon and lime juices. I ended up having close to a half-cup, which is twice what the recipe calls for, but it was all good.

And that’s pretty much it! Here is a photo of the finished salat:

As mentioned above, salat is a traditional accompaniment to many Indian meals, especially those cooked over a fire. I was expecting this colourful dish to be pretty good, in spite of my modifications, but was surprised at just how delicious it was. The crisp, raw vegetables all worked very well together, accented by the bright citrus juice, which had the effect of “pickling” the onions and radishes a bit and toning down the harsh bite that I was expecting. I was also pleased with how well it looked from a visual standpoint; the colours are incredible, and really are part of the enjoyment of the dish, in my opinion.

Altogether, I was very happy with this side dish and expect to use it many more times, especially when cooking South-Asian cuisine.

(later)

From Time/Life’s Foods of the World - The Cooking of India (1969):

By Santha Rama Rau -

Years ago, when I was a child, I went with my mother to spend a couple of months with an aunt who had a large farm in the Punjab, a province in the Northwest of India. The farm is now in Pakistan because the frontier line that was drawn in 1947, separating India from the new Muslim state of Pakistan, severed the Punjab…. I remember [my] meals [there] with a strong sense of nostalgia….

In that part of the country virtually every kitchen has a tandoor, a special kind of clay oven, unknown in the South, and very rare in most other parts of India…. A tandoor is shaped rather like the huge jar in which Ali Baba hid from the Forty Thieves. It is usually sunk neck-deep in the ground…. The charcoal fire on the flat bottom of the jar should heat the sides of the tandoor to a scorching point about halfway up, and to a hot glow for the rest, diminishing, of course, near the neck. To achieve this particular distribution of heat, the tandoor has to be lit at least two hours before anything is cooked in it, and longer if it is not frequently used….

The best known of the tandoori dishes is a chicken preparation for which broilers are skinned, the meat of the breasts and legs carefully cut in slits not quite to the bone, sprinkled with salt and lime juice, and marinated for at least 12 hours. The marinade is a mixture of well-beaten curds and a masala of ground ginger, garlic...chilies, and sometimes saffron (for the colour). If the broilers do not seem tender enough, a piece of green papaya is often added to the masala....

The tandoori chicken, when it is served, should be accompanied by scallions, sliced white radish, wedges of lime, and achar (brine pickles). Often there is a cachumbar as well - chopped cucumber, tomatoes, and onions, sprinkled coriander leaves and slivers of green chilies…. The chicken should be...extremely tender (from the curd marinade), and the spicing [should be] integrally a part of the meat - it should never, that is, be sharp to the palate on the surface and bland inside, but evenly flavoured throughout. The vegetables should always be raw and crisp and served only with salt and a squeeze of lime….

[T]his combination of dishes makes for one of the most popular meals in North India….

Years ago, when I was a child, I went with my mother to spend a couple of months with an aunt who had a large farm in the Punjab, a province in the Northwest of India. The farm is now in Pakistan because the frontier line that was drawn in 1947, separating India from the new Muslim state of Pakistan, severed the Punjab…. I remember [my] meals [there] with a strong sense of nostalgia….

In that part of the country virtually every kitchen has a tandoor, a special kind of clay oven, unknown in the South, and very rare in most other parts of India…. A tandoor is shaped rather like the huge jar in which Ali Baba hid from the Forty Thieves. It is usually sunk neck-deep in the ground…. The charcoal fire on the flat bottom of the jar should heat the sides of the tandoor to a scorching point about halfway up, and to a hot glow for the rest, diminishing, of course, near the neck. To achieve this particular distribution of heat, the tandoor has to be lit at least two hours before anything is cooked in it, and longer if it is not frequently used….

The best known of the tandoori dishes is a chicken preparation for which broilers are skinned, the meat of the breasts and legs carefully cut in slits not quite to the bone, sprinkled with salt and lime juice, and marinated for at least 12 hours. The marinade is a mixture of well-beaten curds and a masala of ground ginger, garlic...chilies, and sometimes saffron (for the colour). If the broilers do not seem tender enough, a piece of green papaya is often added to the masala....

The tandoori chicken, when it is served, should be accompanied by scallions, sliced white radish, wedges of lime, and achar (brine pickles). Often there is a cachumbar as well - chopped cucumber, tomatoes, and onions, sprinkled coriander leaves and slivers of green chilies…. The chicken should be...extremely tender (from the curd marinade), and the spicing [should be] integrally a part of the meat - it should never, that is, be sharp to the palate on the surface and bland inside, but evenly flavoured throughout. The vegetables should always be raw and crisp and served only with salt and a squeeze of lime….

[T]his combination of dishes makes for one of the most popular meals in North India….

Reading the above passage, I was impressed with the influx of knowledge, technique and (using the author’s word) nostalgia that came through the pages, reaching out to me, nearly 50 years later (and by way of her memories, more than 20 years before that), and inspiring me to try this dish. Her descriptions of these meals - not just the food itself, but the time, place, methods and ingredients - paint a picture of Punjabi life that cannot easily be forgotten. My available ingredients and resources necessitated some very slight variations from the author’s description, but I do not feel that the experience was deprived or diminished in the slightest - this was a flat-out wonderful meal, and one that i intend to enjoy many times in the future.

When the time came to actually cook the chicken, I removed the pieces from the masala marinade and laid them out on a tray, brushing each thigh with a splash of ghee:

It was looking great, and it smelling even better! The aromatic mix of spices was an exotic feast in itself; I truly believe that the saffron makes the dish here, in the way that it creates beautiful harmonies with some aromas while bringing other subtle aromas closer to the front. The citrus juices also contribute to a sunny, refreshing ambience that plays an exquisite counter to the earthy spices. The resulting melange is much more than the sum of its parts.

By this time, my Weber Kettle was good and hot, so I laid the chicken out on the grate, positioning it around the central Vortex:

The idea here is that the Vortex concentrates the heat, sending it out to circulate for intense, even heating. It worked very well in my opinion, but please note that your charcoal grill, gas grill or even your oven at high heat will work as well. The Vortex helps you get a little closer to how it's done in India, but there are many ways to skin a cat...or cook a chicken!

Because I elected not to use the red food colouring, the chicken took on a wonderful, roasty-golden brown as it cooked:

One key point is to baste the surface of the chicken pieces now and then with the leftover masala marinade, for flavor, colour and a nice, slightly-crisp exterior. Not too much, but just enough. I also dashed a little bit of ghee onto the chicken during cooking, as well.

By the time they were done, the chicken thighs all looked like wonderful pockets of Punjabi heaven:

What do you think?

Just looking at these photos, I know that I already want to make this again!

In the Punjabi tradition, I served the chicken piled on top of the gorgeous salat:

This created what I consider to be a wonderful feast for the eyes as well as the nose, with the promise of absolute paradise for the palate:

When plating the meal, I tried to keep the parade of colours on exhibition, while also keeping things simple; a simple dusting of garam masala and an opportunity for a splash of lemon and lime was really all that was needed:

This meal was light and - as far as I can determine - quite healthy; it was also very delicious, with the tender, marinated chicken soaking up the earthy spices and bright citrus and ginger highlights. Just as the commentary above describes, the flavours are found throughout the chicken, and not simple concentrated on the surface. It really was unlike anything I have ever had before; but at the same time, it tasted pretty much the way I expected it to - only better!

This recipe, like most from the region, is intended to be just a bit spicier, using hotter peppers; the yogurt or curd in the marinade will tone these down a bit, but for those who are sensitive to hot, spicy foods, my chili powder substitutions as outlined above worked very well, bringing the dish into great balance. Everything worked together - the fabulous chicken with its incredible mix of spices, the crisp, raw vegetables and the piquant pickled foods with the citrus dressing - an amazing symphony that belied the simplicity of the ingredients and the preparation. This was truly one of those meals that gives incredible bang for the buck:

My only regret, and this is 100% my fault, is that this meal screams for a flatbread - any flatbread - and I had none. Even a heated flour tortilla, spread with some ghee, would have been good, allowing the chicken and salat to be wrapped with warm, loving goodness and held in the hand as it was eaten. Due to time constraints, I wasn’t able to make a flatbread for this meal, but I will be sure to do so next time.

I hope that my demonstration of this traditional Punjabi meal will inspire you to try these incredible recipes; they are not the least bit complicated and can be prepared very easily on your grill at home, or in the oven, if need be. You will not be disappointed, and just might find a new favourite.

As always, if there are any questions, please be sure to ask them, and feedback is always welcome. Thank you for taking the time to read this, and if do you do try it, enjoy!

Ron