Post by TasunkaWitko on Sept 21, 2012 11:24:51 GMT -5

Tajine Msir Zitun

Chicken with Lemon and Olives

Often in life, people and circumstances come together at just the right time and place to create an opportunity - a yeastiness - that allows a tiny seed of idea to germinate; under these circumstances, the seed takes root, is nourished, grows, and eventually bears delicious fruit. Such was the case with my first journey to the Maghreb.

I am very eager to learn about the different cuisines across the globe, but due to my limited resources am unable to travel to those far-away places in order to experience the foods that can be found. Some of these gaps can be filled in by reading books; however, there really is no substitute for conversing with people who have actually experienced the real "foods of the world," in a first- or even second-hand encounter. Similarly, I love history, but time travel is not possible (at least, not yet!); so once again, I read - but to touch the past, by going to a place or experiencing the same things that someone would have experienced centuries ago; that truly is the next best thing.

One of the great things about the internet is the fact that people with common interests can come together in online communities and share what they know about things they love; take, for instance, my "Foods of the World" forum:

It is a nexus for many of my major interests: history, cooking, geography, culture, literature, travel and so many others. In creating it, my hope was to attract people who actually had intimate knowledge of things I had only read about. It is nothing short of a technological miracle that a regular joe in Montana can immediately converse with friends - not just in his own country, but also around the world - in an effort to learn more about such things.

This project is a prime example of that notion. I had done some reading about "the cooking of the Maghreb;" I found it interesting indeed, but filed it away in some dusty corner of my mind, assuming that the concepts, ingredients and methods were so esoteric - so foreign - that I would never be able to actually create it; so, there wasn't really any point in considering the matter further.

Thanks to many of my friends here at FotW, I discovered just how wonderfully wrong I was! Through many conversations here, the idea of creating authentic North African food and enjoying it began to seem like an achievable goal. This epiphany probably began when I saw Margi's easy sea bass tajine from Tangier:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/tangier-sea-bass-tagine_topic1727.html

Looking over that recipe and reading the easy, step-by-step method was like having a light bulb switch on in my head, and I noticed that something I had read about that seemed intricate and complicated, really wasn't difficult at all. Oh, sure - there were a lot of ingredients, some of which I had never really been exposed to, but they were indeed available (substituting another fish for the sea bass and "regular" paprika for smoked) and the actual method was indeed quite easy. The wheels began to turn, and I took a fresh look at recipes that had been languishing in obscurity here for some time, such as Dave's Moroccan chicken, with its easy, step-by-step instructions:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/moroccan-chicken_topic148.html

And John's El Lahm el M'qali:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/el-lahm-el-mqali_topic669.html

A good deal of inspiration came from these posts, as they provided tempting "peeks" into the joys of North African cuisine. Much inspiration also came from Ahron at about the same time, when he posted some pictures showing just how exciting and exotic it can be to eat in Morocco:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/food-in-morocco_topic1874.html

Sure, I had read about Moroccan food, and I had even seen pictures of colorful, exotic feasts laid out in some books - but to actually talk with someone who had been there and who had eaten the very same food as shown in the pictures! And to see the same things he saw! It was truly a thing that fostered my desire, and I wanted to see what it was like.

Through the prism of this new perspective, these dishes took on an entirely fresh brilliance, and my interest, as well as my imagination, was kindled. It was still intimidating, but I began to think that it was at least possible; thanks to the conversations with and patience of my online friends, mentioned above and also below, I gradually acquired the inspiration, the knowledge and the confidence needed to take the first small steps as I proceeded to transform the desire into reality. This pictorial, documenting my own experience, is my attempt to introduce you, Dear Reader, to North African cooking, in the hope that your own interest will be sparked and you will be inspired to see just how easy it is to journey across the world and travel back in time, simply by cooking a dish that would have been cooked centuries ago by someone in a remote location on the other side of the globe.

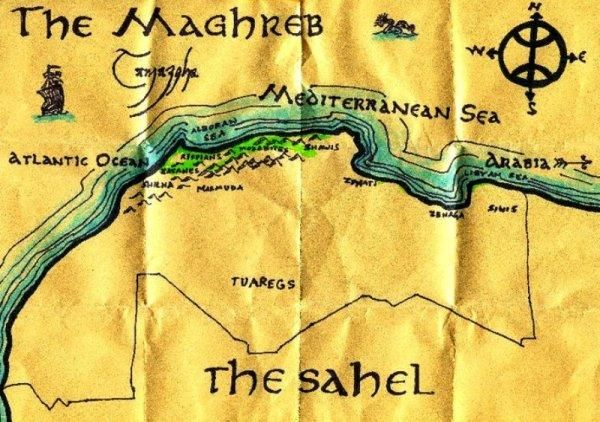

In order to cross the gateway into the cooking of the Maghreb, it is helpful to know what the Maghreb is, and to learn a few things about its culinary history that make it such a worthy destination. This passage, adapted from www.ancientworlds.net, along with a few photos that I found on the internet, will provide some of the back-story:

Michael Field, writing for Time-Life, made a similar discovery during his first trip to the Maghreb; initially, he had concerns about the tumultuous history of the region and its effect on the individuality of North African cuisine; however, it seems that by the time he left the Maghreb, he had found his answer:

One day in that balmy period between late winter and early spring, it all came together for me, as the last piece of the puzzle fell into place. During a trip to Billings, I dropped into a World Market:

www.worldmarket.com

And on a shelf in a far corner, I spied this:

The primary piece of cookware in North African cooking is the tajine (also spelled tagine). This vessel is truly unique and is well-adapted to cooking in the Maghreb, as we shall see later; however, the word tajine itself is one of those rare, special, multilayered words with many purposes, as Field discovered in the course of his visit to North Africa:

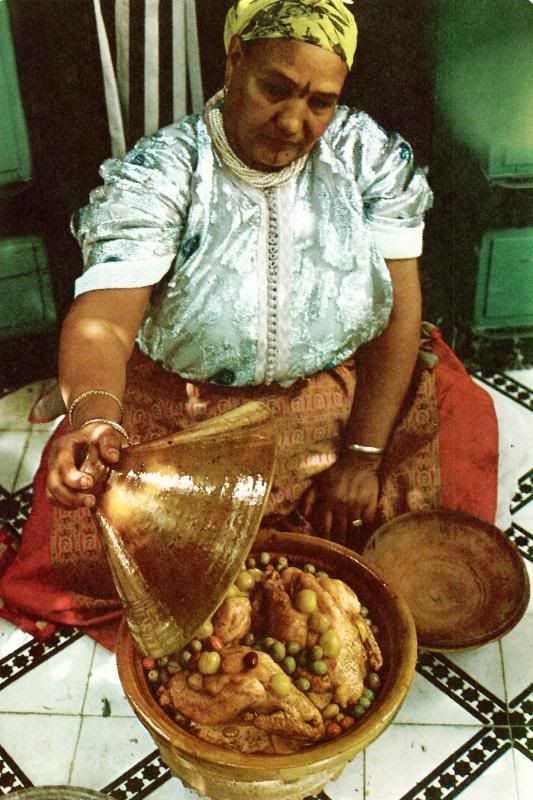

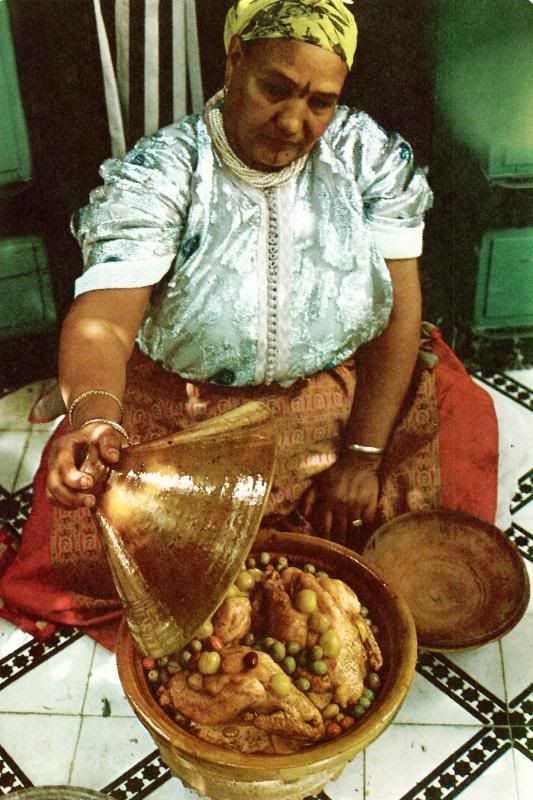

Photo Credit: Time/Life's Foods of the World - a Quintet of Cuisines, 1970

With all this in mind, I snatched up one of the tajines from the shelf and carefully transported it 240 miles back home, finally committed to attempting a Maghrebi cooking project.

Even though a tajine (cookware) is not absolutely necessary to create a tajine (dish), it is, as mentioned above, designed specifically for the kind of cooking that makes the most out of the ingredients used; a product evolved in the Maghreb, for Maghreb cooking. Aside from this, it goes a long way in setting the atmosphere - like many of the ingredients unique to Moroccan cooking - and brings you a little closer to achieving the goal of experiencing the time and place we are dealing with.

If you do decide to get a tajine, there are a few things to remember: First, there are cooking tajines, designed to cook with, and there are serving tajines, designed for plating and presentation. Assuming that you have a cooking tajine, it will need to be "cured," unless it is completely, 100% glazed on all surfaces. If in doubt, cure it anyway, since it is easy to do. To cure your tajine, start by submerging it in water over-night; the next day, wipe a thin film of olive oil on all surfaces of the tajine, place it into a cold oven. Turn on the oven and heat the tajine at 300 degrees for a couple of hours, then shut off the oven and let the tajine cool down naturally in the oven. This will take several hours, since the tajine holds heat incredibly well. Your tajine will now be ready for use; be aware that the curing process can cause tiny cracks in the glaze and also some darkening with patina. This is completely normal and even desirable in some ways. Something else to keep in mind is that your tajine is most likely designed to be used in the oven only; I would not recommend using a terra cotta tajine - glazed or otherwise - on the stove-top, with the possible exception of cooking over low heat in conjunction with a heat diffuser. You can achieve perfectly delicious and even wonderful results by using your tajine in the oven, so it simply isn't worth the risk of cracking or shattering your tajine due to heat stress.

Enough talk - let's get to making this! Here's the recipe, from Time/Life's Foods of the World - a Quintet of Cuisines, 1970:

I was pleasantly surprised at how easy this was to make, and how smoothly the preparation flowed. Cooking with a tajine is another one of those projects that I had been putting off, due to a perception that it would be complicated, intricate or otherwise difficult, and I was intimidated by the perceived challenge and risk of failure. In this case, as in so many others, I was proven completely wrong - it was easy! My advice, if you have any interest at all in trying this, is to put aside any concerns you might have and simply give it a go - you will be glad that you did!

Something be aware of is that this is truly a dish from antiquity. The "youngest" ingredient in the recipe is the paprika, which dates back to the 16th Century and is, by all definitions, ancient; but one should keep in mind that it would be just as easy to remove that component and go back over a thousand years with this dish. When you stop and think about that, things take on a whole level of significance; it's almost like time travel.

Here's a shot of the goods, as per the recipe:

As you can see, there's nothing there that really would be considered exotic or hard-to-get. The sole exception might be the smoked paprika, which I chose to use in lieu of the "regular" paprika specified in the recipe; in other words, use whatever paprika you wish, the higher-quality the better. If you are able to get your hands on some smoked paprika, however, you will be rewarded with a truly unique experience that, in my opinion, brings you much closer to a verdant oasis in the middle of the desert under a clear, starry sky and crescent moon. One convenient source for smoked paprika is the internet, where it can be found at places such as www.amazon.com or www.latienda.com, where it is marketed as pimentón de la vera.

If you look to the left in the photo, you will see a jar of msir, which is nothing more than lemons that have been "dried" by quartering and salting them, as Field discovered in Morocco:

This tajine can be made without them, but I will say that these are, in my opinion, essential to the dish if one really wants to experience it, and there is no reason to go without them, especially since they are so easy to make. More on this in a moment....

But it looks to me as though something is missing - what could it be?

Ah, yes - the chicken!

For this preparation, I chose to use 9 boneless, skinless chicken thighs, which are full of flavour. The truth is, however, you can use any combination of chicken: a whole, cut up chicken, breasts, legs, bone-in, skin-on, Cornish game hens - whatever you prefer. For that matter, you can also use any number of various game birds such as dove, partridge, quail, squab, grouse, pheasant or chukar.

mise en place is pretty straightforward; simply dice your onion:

And measure your spices:

Clockwise from the top: smoked paprika, ginger, turmeric, salt and pepper.

Next, drain your olives and dump them into a bowl:

This is probably not necessary, but a lot can be said for being organised and ready, because things can and often do happen fast in the kitchen.

For some reason, I really went wild and combined jumbo black olives with smaller green olives, but no worries; you can use any olives you like, of any size you prefer. When using olives at the smaller end of the scale, however, you might want to double the amount.

The final piece of prep work involved the msir. As I said before, these are nothing more than lemons that have been naturally "dehydrated" by applying salt to them. Here is a link that gives an in-depth explanation and step-by-step pictures on how to do this:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/msir-moroccan-salted-dried-lemons_topic479.html

For those wanting a quick summary, you simply need to wash your lemons, cut their ends off, stand them up on end, quarter them "the long way" almost completely through, gently open them up like a flower, apply a little salt to the surfaces of the pulp inside, then close the "flower." Pack the lemons into a jar and place the jar somewhere where it can be undisturbed for at least two weeks while the salt works its magic; during that time, you might want to to rotate the jar periodically - in order to distribute the salt - and crack the lid open, in order to release built-up pressure. At the end of two weeks, and periodically after that, open the jar and pour off any accumulated juice. It won't take long until the effects of the salting will become evident; the lemons actually will "dry out," and will be able to be stored in the jar - with or without refrigeration - for a very long time, until ready for use. This preservation technique is essential in the hot, dry climate of the Maghreb, and it lends a great amount of authenticity to many varieties of tajines; however, if you do not have any msir on hand, and do not have time to make any, you can still make a perfectly acceptable tajine using fresh lemons. Probably any tajine recipe would respond well, but you should have especially good results using Brook's recipe here, which doesn't call for msir:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/lemon-chicken-tajine_topic1852.html

Anyway, proceeding forward, here is how to prepare the msir so that they will be ready to be used in this dish. Take two lemons' worth (8 quarters in all) and if they are not already separated, go ahead and do so. Next, run a good, sharp, thin-bladed knife such as a fillet knife between the pulp and the peel, thusly:

This will leave you with a segment that is composed primarily of peel:

Then, simply dice the segments into small pieces:

Leaving you with this:

This dicing step is not mentioned in the recipe; however, it made intuitive sense to do so at the time; one can leave the quarters whole, or cut them up for even distribution, as preference or whim dictates.

I tried one of the pieces and was amazed at the truly unique flavour that it had. It was had a fresh, acidic, intensely-lemony taste, with a slightly salty accent and just a suggestion of bitterness from the peel to balance everything out. Impressive, to be sure; as I said above, it really transports you to the Maghreb, and even though you can use fresh, "unpreserved" lemons, I strongly believe that your tajine experience is somewhat incomplete with msir.

Enough prep work - let's get to cooking this stuff!

A person could simply combine the ingredients in a tajine and cook it that way, resulting in a completely authentic tajine; however, I chose to go an extra step and do some pre-browning - which as far as I can tell is also practiced in North Africa - both for flavour and in order to get a head start on the cooking of the dish.

Keepng in mind that I would be adding more seasoning later, I very-lightly salted and peppered the chicken thighs, then seared them in batches in a little hot olive oil, using my cast iron Dutch oven:

In North Africa, this step would most likely be done in the tajine itself over a low flame; however, using an electric stove, I was concerned about cracking my tajine due to heat stress - not having a heat diffuser, I chose to use the cast iron.

Keep in mind that you do not want to cook the chicken all the way through; the goal is to get some browning on the outside of the chicken and warm it up a bit. Here, they are not quite browned enough:

So I turned them over a couple of times and continued to cook them until they took on a beautiful, golden sear.

In the picture above, note the fond that is developing on the bottom of the Dutch oven; this will become extremely wonderful, deep flavour later on as the chicken braises in the tajine.

Once all the pieces were nicely browned; I placed them in the tajine:

As I said before, a tajine is not absolutely, 100% necessary in order to make this dish; you can easily find and purchase a tajine on the internet, using online sources such as or, if you are close to a store such as World Market, you can get one there:

www.worldmarket.com

However, if you absolutely want to make this right now and don't have a tajine, a covered casserole, Dutch oven, slow cooker or baking dish will give acceptable results. If you choose to go this route, I would suggest consulting Chris's outstanding "Tajine sans Tajine" thread here:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/tajine-sans-tajine-the-easy-diy-approach_topic2171.html

The methods that he outlines will be useful with this recipe, or probably any other that you would like to try, using non-traditional or modern cookware.

It is here that I did make one mistake in the preparation of this dish; the instructions state that the msir should be added toward the end, during the last 5 minutes or so of cooking; however, I forgot that little bit of advice, and added them here:

No real worries, as the dish seemed to turn out just fine, but it is something to be aware of as I am sure that the lemon was infused into the dish somewhat more than probably intended; this can be good - or not-so-good - depending on your outlook.

In any case, once the chicken is browned, things start moving forward fairly quickly. Carefully - so as not to disturb the wonderful, beautiful fond - drain off any excess oil, leaving a tablespoon or so. Then, bring up the heat a little and toss in the onions, stirring them around to pick up the fond while they caramelise:

When the onions just start to take on a golden-brown appearance at the edges, remove from the heat and toss in your spices, stirring to coat:

The reason for removing your cooking vessel from the heat is because many herbs and spices, particularly paprika, run the risk of scorching when added to direct heat; this will have many negative consequences, including but not limited to scorched flavour, grittiness and blackening. Having said that, many spices, particularly paprika, really come into their own when combined with heat and fat, releasing beautiful, deep colours and rich, wonderful aromas and flavours. It is a fine line to walk, but once you learn to navigate it, the food you cook will take on a whole new level of complex goodness.

Once the spices are worked into the fat and thoroughly incorporated into the onions, add the water:

Broth or stock could also be used, adding yet one more layer to the masterpiece that will become your dish; if you go with broth or stock, keep the salt content in mind during preparation.

Bring the mixture to a simmer, stirring frequently and taking care to lift any residual bits that might be stuck to the bottom of the pan, then pour all of this into the tajine on top of the chicken and msir:

The beauty of braising in general, and tajine cooking in particular, is that the steam from cooking will rise up, condense in the lid, and then run back down the inside of the lid in order to keep the food moist, tender and juicy. A little bit of liquid is all you need (in this case, a cup or a cup-and-a-half, at most), and the small amount of evaporation that does take place will serve to reduce the resulting juices down to a rich, flavourful sauce.

Next, run a thin scrim of olive oil around the rim of the tajine lid, in order to help with sealing, then place the tajine in a cold oven and turn it on to 325. Alternately, I suppose that simmering could take place on the stove-top, but as I said before, I was very reluctant to try this without a heat diffuser; besides, it seemed to me that an oven would be better for heating the dish from all sides.

While this concoction was simmering in the oven, a beautiful thing began to happen; the entire house was slowly filled with warm, wonderful aromas as the spices intermingled with the chicken, onion, msir and other components of the dish. It was all one could do to not lift the lid and take a peek - but such self-discipline is one of the things that separates us from the animals, so we resisted the urge.

Since I was cooking at a tajine-safe temperature that was lower than the one in the recipe, I added 15 or 20 minutes to the total proscribed cooking time. After an hour or so, we removed the tajine from the oven, checked the chicken for doneness and added the olives:

It was here that I realised this is where I should have added the misr, according to the recipe, but no worries; also, as mentioned above, the vast difference in the sizes of the olives was a bit awkward, but in the end they tasted great, and that's what mattered.

I returned the tajine to the oven for another 5 or 10 minutes, and then removed the dish from the oven and took a look at what I had created:

Well, I would call that a success, especially for a first time - and so easy - I really can't get across to you just how easy this was; you're just going to have to try it for yourself and see!

The traditional accompaniment for most tajines is couscous. I had been wondering about the best way to go about this, when I noticed the still-bubbling cooking liquid in the tajine:

This sight resulted in a flash of inspiration, and I quickly acted on it. First, I removed the chicken pieces to a covered dish in order to keep warm; then, I dumped a box of couscous into the tajine,gave it a quick, gentle stir to distribute it, and returned the lid so that the pasta could absorb the cooking liquids - along with all of the wonderful flavours therein. Couscous takes only a few moments to cook, due to the very small size of its grains, and it seemed to me that this method must be so obvious as to be consistent with methods in North Africa. Some sources mention steaming the couscous above the food as it cooks, but this improvisation seemed practical and easy, achieving the same results, so I did it this way. My only concern was whether there would be enough liquid to fully reconstitute the pasta, so I added jsut a little more boiling water to the tajine and waited another minute or three, and it seemed to work very well, soaking up the excess liquid and leaving behind a wonderful sauce. A small test-sampling of the couscous revealed that it was cooked perfectly and full of rich, lively bits of flavor from the onion and msir, brought together by the savory chicken broth, earthy spices and other components in the cooking liquid - but there was indeed something more than this - just a little extra goodness that I would attribute to the magic of the Maghreb!

I served this seemingly humble, yet majestic dish with a simple salad of vinegar-soaked cucumbers topped with tzatziki:

By now, after going through the preparation steps for it, smelling it during cooking, a quick look when I added the olives and that tantalizing, oh-too-brief sample of couscous to see if it was ready, my mouth was watering and I was ready to experience this dish - and I wasn't disappointed at all. I knew that it was going to be good, bordering on fantastic, but I was unprepared for the absolute symphony that erupted in my mouth, bringing together savory depth, earthy warmth, citrusy accents and so many other things to the party. It was easily one of the most impressive dishes I have made, which is surprising, considering the relatively humble nature of the ingredients, when considered individually. It was still amazing to me that this rich, complex, exotic-tasting dish could be so incredibly easy to prepare; and yet, the proof of this was bringing my taste buds to their knees with pleasure.

The rest of the family enjoyed it in general, but the beautiful Mrs. Tas, while indeed liking the meal over-all, didn't care for the mouth feel of the couscous, with its smaller-than-rice grains of pasta, and wasn't impressed with the lemon aspect. As for myself, I was thoroughly impressed with the whole thing, especially the way the flavours married in the tajine in order to produce something that was so much more than the sum of their individual roles. I'll definitely be doing this and other tajine dishes in the future.

This was once again an example of how some guy in Montana - pretty much a novice at cooking and completely unfamiliar with the mystique of the Maghreb, was able to take himself and his family on a journey through time and space, with the help and encouragement of the friends he had made and the experiences they had had. We were once again transported across the sea - this time to that aforementioned, lush oasis in North Africa under the crescent moon of a star-filled sky. It could have been that this very same dish was served in a Moroccan household the night before, or even hundreds of years ago, when oriental spices - and their trade - created and destroyed empires.

My sincere thanks to Dave, Margi, Brook, Ahron, Chris, John, and others who not only opened the door for me, but also gave me the kick in the rear to go through it. When we study, create and share experiences such as this, we truly are preserving that distant past, so that the distant future might perhaps remember and benefit from it. I do hope that you are inspired to give this a try, and that I have drawn a clear map for your journey; however, if you have any questions, just ask, and they shall be answered.

Chicken with Lemon and Olives

Often in life, people and circumstances come together at just the right time and place to create an opportunity - a yeastiness - that allows a tiny seed of idea to germinate; under these circumstances, the seed takes root, is nourished, grows, and eventually bears delicious fruit. Such was the case with my first journey to the Maghreb.

I am very eager to learn about the different cuisines across the globe, but due to my limited resources am unable to travel to those far-away places in order to experience the foods that can be found. Some of these gaps can be filled in by reading books; however, there really is no substitute for conversing with people who have actually experienced the real "foods of the world," in a first- or even second-hand encounter. Similarly, I love history, but time travel is not possible (at least, not yet!); so once again, I read - but to touch the past, by going to a place or experiencing the same things that someone would have experienced centuries ago; that truly is the next best thing.

One of the great things about the internet is the fact that people with common interests can come together in online communities and share what they know about things they love; take, for instance, my "Foods of the World" forum:

It is a nexus for many of my major interests: history, cooking, geography, culture, literature, travel and so many others. In creating it, my hope was to attract people who actually had intimate knowledge of things I had only read about. It is nothing short of a technological miracle that a regular joe in Montana can immediately converse with friends - not just in his own country, but also around the world - in an effort to learn more about such things.

This project is a prime example of that notion. I had done some reading about "the cooking of the Maghreb;" I found it interesting indeed, but filed it away in some dusty corner of my mind, assuming that the concepts, ingredients and methods were so esoteric - so foreign - that I would never be able to actually create it; so, there wasn't really any point in considering the matter further.

Thanks to many of my friends here at FotW, I discovered just how wonderfully wrong I was! Through many conversations here, the idea of creating authentic North African food and enjoying it began to seem like an achievable goal. This epiphany probably began when I saw Margi's easy sea bass tajine from Tangier:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/tangier-sea-bass-tagine_topic1727.html

Looking over that recipe and reading the easy, step-by-step method was like having a light bulb switch on in my head, and I noticed that something I had read about that seemed intricate and complicated, really wasn't difficult at all. Oh, sure - there were a lot of ingredients, some of which I had never really been exposed to, but they were indeed available (substituting another fish for the sea bass and "regular" paprika for smoked) and the actual method was indeed quite easy. The wheels began to turn, and I took a fresh look at recipes that had been languishing in obscurity here for some time, such as Dave's Moroccan chicken, with its easy, step-by-step instructions:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/moroccan-chicken_topic148.html

And John's El Lahm el M'qali:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/el-lahm-el-mqali_topic669.html

A good deal of inspiration came from these posts, as they provided tempting "peeks" into the joys of North African cuisine. Much inspiration also came from Ahron at about the same time, when he posted some pictures showing just how exciting and exotic it can be to eat in Morocco:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/food-in-morocco_topic1874.html

Sure, I had read about Moroccan food, and I had even seen pictures of colorful, exotic feasts laid out in some books - but to actually talk with someone who had been there and who had eaten the very same food as shown in the pictures! And to see the same things he saw! It was truly a thing that fostered my desire, and I wanted to see what it was like.

Through the prism of this new perspective, these dishes took on an entirely fresh brilliance, and my interest, as well as my imagination, was kindled. It was still intimidating, but I began to think that it was at least possible; thanks to the conversations with and patience of my online friends, mentioned above and also below, I gradually acquired the inspiration, the knowledge and the confidence needed to take the first small steps as I proceeded to transform the desire into reality. This pictorial, documenting my own experience, is my attempt to introduce you, Dear Reader, to North African cooking, in the hope that your own interest will be sparked and you will be inspired to see just how easy it is to journey across the world and travel back in time, simply by cooking a dish that would have been cooked centuries ago by someone in a remote location on the other side of the globe.

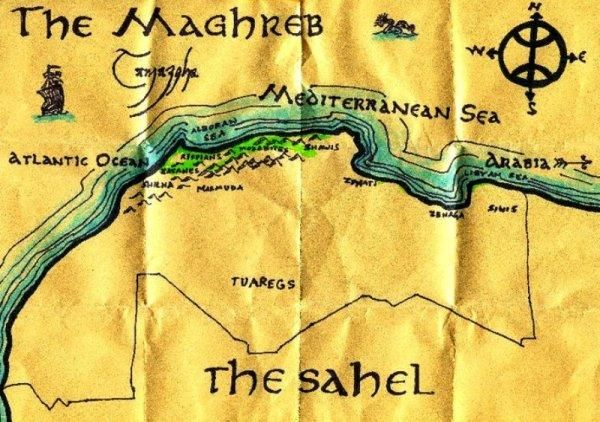

In order to cross the gateway into the cooking of the Maghreb, it is helpful to know what the Maghreb is, and to learn a few things about its culinary history that make it such a worthy destination. This passage, adapted from www.ancientworlds.net, along with a few photos that I found on the internet, will provide some of the back-story:

The countries of Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria, because of their indigenous people, history, and unique geographical position, have a culinary tradition quite different from the rest of the African continent. These three countries are known as the Maghreb from the Arabic for “the land farthest west;” two thousand years ago the three countries were one....

Photo Credit: www.amoeba.com/dynamic-images/blog/Eric_B/photo-3.jpeg

Cooking in the Maghreb has been influenced by [many cultures, including the Carthaginians,] the Persians, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Ottoman Turks, Spanish, British, and French.

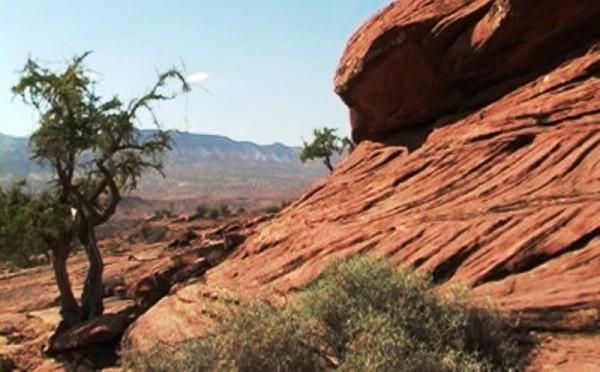

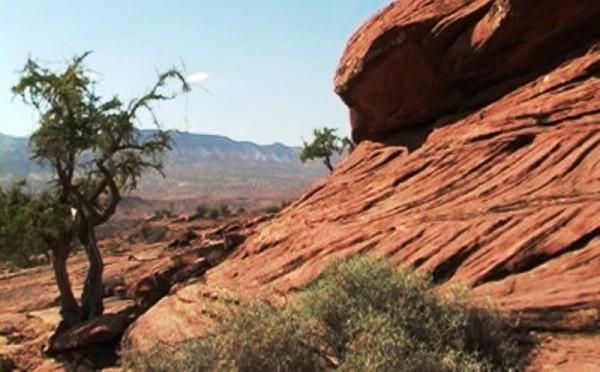

Photo Credit: www.seven-continents.com/argana-tal-marokko.JPG

The Carthaginians are thought to have introduced durum wheat in the form of semolina, which became the staple of the region, couscous. When the Romans expelled the Carthaginians, they named the region Mauretania Tingitana (it is from this name that the term “Moors” about). The Romans made this region the “breadbasket” of its empire, and the Maghreb supplied the empire with...wheat and other grains it needed to feed its people and its armies....

Photo Credit: members.bib-arch.org/bswb_graphics/BSAO/04/04/BSAO040404400.jpg

The most lasting effect on the region came in the year 683, when Morocco was invaded by the Arabs. The Arabs were the world’s spice merchants for many centuries and they introduced cinnamon, saffron, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg to North Africa. The Arabs went on to conquer Spain in 711. Known as the Moors, they kept North Africa connected to Spain for centuries [in the form of a province called al-Andalus].

Photo Credit: assets0.blurb.com/images/uploads/catalog/56/93256/527226-c19c27b9fca86ebb513c953d8b54d47b.jpg?20120730184813

The Arabs brought their religion and the culture of the Middle East, [and also] brought citrus and olives back to North Africa from Spain...this helped to fuse the ingredients of the Mediterranean with those of the Maghreb. When the Spanish Moors and Sephardic Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many chose to settle in Morocco, and they brought their cuisines with them....

Photo Credit: www.gojerusalem.com/_media/userfiles/8/13698/83980.jpg

The Ottoman Turks were repelled from ever crossing into Moroccan territory, and so the Ottoman Empire did not have as much influence on the cuisine of Morocco as it did elsewhere. Portuguese and Spanish influence in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries introduced the region to the New World; chiles and tomatoes had a powerful impact on the tastes of the Maghreb....

Photo Credit: www.umbc.edu/mll/Espaces/Espaces-theMaghreb/Maghreb%20images/500px-Skala.jpg

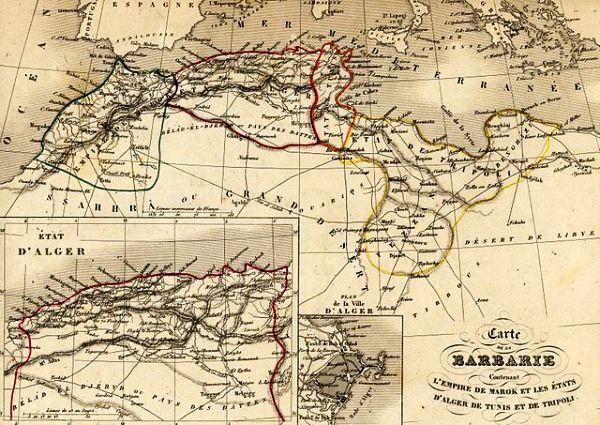

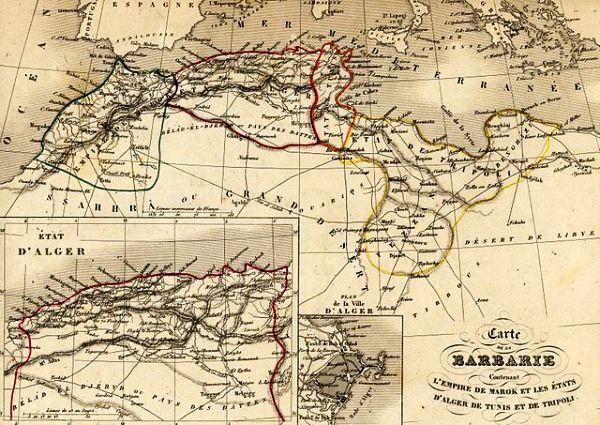

France...annexed Algeria in 1834, and at the beginning of the twentieth century Britain struck a deal with France: the French could keep control over Morocco in exchange for British control in Egypt. The French influence in the region was greatest in Algeria, but it provided an elegance in presentation of food in all of the countries in North Africa.

Photo Credit: upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Carte_Maghreb_Vuillemin_1843.jpg

Moroccan cuisine is a Mediterranean cuisine, with reliance on lemons, olives, olive oil, and garlic. Persian influence can be seen in Morocco’s taste for meats combined with fruits and the use of “sweet” spices in savory dishes. It is spice that characterizes Moroccan food. Brought to Morocco [via caravan trade routes] were ginger, turmeric, saffron, black peppercorns, coriander, cumin, cinnamon, paprika, and garlic. A surprising spice to be found in the region is caraway, normally associated with foods of northern Europe.

Photo Credit: www.seven-continents.com/morocco.JPG

Favorite meats include lamb, beef, and poultry, with a fondness for pigeon or squab. With a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, fish is also quite popular. Sardines are especially enjoyed throughout the Maghreb.

Photo Credit: 3.bp.blogspot.com/-U2SRG2QLMtc/TkKVhLe1EAI/AAAAAAAABGc/FtYWpPt6wko/s1600/The_Mediterranean_Sea_Sardinia.JPG

The staple in Morocco (and across the region) is couscous. Couscous is often steamed by placing it over a simmering tagine, with the flavors of the stew infused into the small pasta kernels. It may be flavored with butter, spices, vegetables, and meats. It can be served alone or accompanied by a rich tagine. Tagines are wonderfully flavorful stews, slowly cooked in a special ceramic cooking vessel.

There is a Maghrebi proverb to the effect that Algeria is the man, Tunisia is the woman, and Morocco is the lion. The food of Morocco certainly lives up to this analogy. Moroccan cuisine is assertive and aggressive, with liberal use of a multitude of spices....

Photo Credit: www.amoeba.com/dynamic-images/blog/Eric_B/photo-3.jpeg

Cooking in the Maghreb has been influenced by [many cultures, including the Carthaginians,] the Persians, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Ottoman Turks, Spanish, British, and French.

Photo Credit: www.seven-continents.com/argana-tal-marokko.JPG

The Carthaginians are thought to have introduced durum wheat in the form of semolina, which became the staple of the region, couscous. When the Romans expelled the Carthaginians, they named the region Mauretania Tingitana (it is from this name that the term “Moors” about). The Romans made this region the “breadbasket” of its empire, and the Maghreb supplied the empire with...wheat and other grains it needed to feed its people and its armies....

Photo Credit: members.bib-arch.org/bswb_graphics/BSAO/04/04/BSAO040404400.jpg

The most lasting effect on the region came in the year 683, when Morocco was invaded by the Arabs. The Arabs were the world’s spice merchants for many centuries and they introduced cinnamon, saffron, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg to North Africa. The Arabs went on to conquer Spain in 711. Known as the Moors, they kept North Africa connected to Spain for centuries [in the form of a province called al-Andalus].

Photo Credit: assets0.blurb.com/images/uploads/catalog/56/93256/527226-c19c27b9fca86ebb513c953d8b54d47b.jpg?20120730184813

The Arabs brought their religion and the culture of the Middle East, [and also] brought citrus and olives back to North Africa from Spain...this helped to fuse the ingredients of the Mediterranean with those of the Maghreb. When the Spanish Moors and Sephardic Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492, many chose to settle in Morocco, and they brought their cuisines with them....

Photo Credit: www.gojerusalem.com/_media/userfiles/8/13698/83980.jpg

The Ottoman Turks were repelled from ever crossing into Moroccan territory, and so the Ottoman Empire did not have as much influence on the cuisine of Morocco as it did elsewhere. Portuguese and Spanish influence in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries introduced the region to the New World; chiles and tomatoes had a powerful impact on the tastes of the Maghreb....

Photo Credit: www.umbc.edu/mll/Espaces/Espaces-theMaghreb/Maghreb%20images/500px-Skala.jpg

France...annexed Algeria in 1834, and at the beginning of the twentieth century Britain struck a deal with France: the French could keep control over Morocco in exchange for British control in Egypt. The French influence in the region was greatest in Algeria, but it provided an elegance in presentation of food in all of the countries in North Africa.

Photo Credit: upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/Carte_Maghreb_Vuillemin_1843.jpg

Moroccan cuisine is a Mediterranean cuisine, with reliance on lemons, olives, olive oil, and garlic. Persian influence can be seen in Morocco’s taste for meats combined with fruits and the use of “sweet” spices in savory dishes. It is spice that characterizes Moroccan food. Brought to Morocco [via caravan trade routes] were ginger, turmeric, saffron, black peppercorns, coriander, cumin, cinnamon, paprika, and garlic. A surprising spice to be found in the region is caraway, normally associated with foods of northern Europe.

Photo Credit: www.seven-continents.com/morocco.JPG

Favorite meats include lamb, beef, and poultry, with a fondness for pigeon or squab. With a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, fish is also quite popular. Sardines are especially enjoyed throughout the Maghreb.

Photo Credit: 3.bp.blogspot.com/-U2SRG2QLMtc/TkKVhLe1EAI/AAAAAAAABGc/FtYWpPt6wko/s1600/The_Mediterranean_Sea_Sardinia.JPG

The staple in Morocco (and across the region) is couscous. Couscous is often steamed by placing it over a simmering tagine, with the flavors of the stew infused into the small pasta kernels. It may be flavored with butter, spices, vegetables, and meats. It can be served alone or accompanied by a rich tagine. Tagines are wonderfully flavorful stews, slowly cooked in a special ceramic cooking vessel.

There is a Maghrebi proverb to the effect that Algeria is the man, Tunisia is the woman, and Morocco is the lion. The food of Morocco certainly lives up to this analogy. Moroccan cuisine is assertive and aggressive, with liberal use of a multitude of spices....

Michael Field, writing for Time-Life, made a similar discovery during his first trip to the Maghreb; initially, he had concerns about the tumultuous history of the region and its effect on the individuality of North African cuisine; however, it seems that by the time he left the Maghreb, he had found his answer:

Frances and I looked forward to our first visit to North Africa with equal excitement but - as usual when we travel together - with different expectations. She had read a great deal about North Africa's history and the religion of its predominantly Muslim populations; my eye was fixed firmly on North Africa's culinary compass, although I found its needle swinging disconcertingly in every direction. Would the cuisine be the classic one Tunisians, Algerians and Moroccans proudly claim it to be? Or would each country's cooking elude definition, mirroring the culinary traditions of various rulers across the centuries?

It was while flying back to New York that I began slowly and objectively to [realize] that North Africa's claim to a cuisine of its own is unquestionably true. While not as sophisticated and complex as the French cuisine nor so varied and subtle as the Chinese, the cooking of the Maghreb combines all those attributes in a way that makes it utterly distinctive. I found myself thinking about it in musical terms, as I often do when deeply moved, and I still think of it that way: as a three-movement symphony held together by interlocking themes: - Tunisia, a lively, fiery first movement, allegro con brio; pastoral Algeria, a slow andante; and Morocco, richest of all, a grand finale maestoso. Altogether a magnificent whole, not yet fully known or appreciated by the rest of the world.

It was while flying back to New York that I began slowly and objectively to [realize] that North Africa's claim to a cuisine of its own is unquestionably true. While not as sophisticated and complex as the French cuisine nor so varied and subtle as the Chinese, the cooking of the Maghreb combines all those attributes in a way that makes it utterly distinctive. I found myself thinking about it in musical terms, as I often do when deeply moved, and I still think of it that way: as a three-movement symphony held together by interlocking themes: - Tunisia, a lively, fiery first movement, allegro con brio; pastoral Algeria, a slow andante; and Morocco, richest of all, a grand finale maestoso. Altogether a magnificent whole, not yet fully known or appreciated by the rest of the world.

One day in that balmy period between late winter and early spring, it all came together for me, as the last piece of the puzzle fell into place. During a trip to Billings, I dropped into a World Market:

www.worldmarket.com

And on a shelf in a far corner, I spied this:

The primary piece of cookware in North African cooking is the tajine (also spelled tagine). This vessel is truly unique and is well-adapted to cooking in the Maghreb, as we shall see later; however, the word tajine itself is one of those rare, special, multilayered words with many purposes, as Field discovered in the course of his visit to North Africa:

Picking up a shallow, covered ceramic pot much like one of our casseroles, I asked Abdul in French what it was. "Tajine," he answered, then attempted to explain something that made little sense to me. Frustrated, I lifted the chicken by its feet, and pointing to the vegetables and other ingredients, made a stirring motion with my forefinger in the empty tajine. My pantomime seemed ineffectual. Abdul merely smiled again and said, "Tajine," indicating the pot with one hand, the ingredients in the other. At last it dawned on me that the tajine was both the pot and the dish.

Suddenly there occurred the subliminal communication that takes place between cooks everywhere despite language and nationality. I quickly understood that any combination of ingredients, however disparate, was called a tajine if cooked in a tajine. One we had established this much rapport, Abdul set to work, apparently confident that I would understand everything else he was going to do.

Suddenly there occurred the subliminal communication that takes place between cooks everywhere despite language and nationality. I quickly understood that any combination of ingredients, however disparate, was called a tajine if cooked in a tajine. One we had established this much rapport, Abdul set to work, apparently confident that I would understand everything else he was going to do.

Photo Credit: Time/Life's Foods of the World - a Quintet of Cuisines, 1970

Sitting on the floor of a kitchen in Marrakech, a Moroccan cook applies the finishing touches to a tajine msir zitun, which she has cooked in an earthenware tajine slaoui. Actually, tajine applies to any dish cooked in a tajine slaoui.... In its many variations, it is a favourite throughout North Africa.

With all this in mind, I snatched up one of the tajines from the shelf and carefully transported it 240 miles back home, finally committed to attempting a Maghrebi cooking project.

Even though a tajine (cookware) is not absolutely necessary to create a tajine (dish), it is, as mentioned above, designed specifically for the kind of cooking that makes the most out of the ingredients used; a product evolved in the Maghreb, for Maghreb cooking. Aside from this, it goes a long way in setting the atmosphere - like many of the ingredients unique to Moroccan cooking - and brings you a little closer to achieving the goal of experiencing the time and place we are dealing with.

If you do decide to get a tajine, there are a few things to remember: First, there are cooking tajines, designed to cook with, and there are serving tajines, designed for plating and presentation. Assuming that you have a cooking tajine, it will need to be "cured," unless it is completely, 100% glazed on all surfaces. If in doubt, cure it anyway, since it is easy to do. To cure your tajine, start by submerging it in water over-night; the next day, wipe a thin film of olive oil on all surfaces of the tajine, place it into a cold oven. Turn on the oven and heat the tajine at 300 degrees for a couple of hours, then shut off the oven and let the tajine cool down naturally in the oven. This will take several hours, since the tajine holds heat incredibly well. Your tajine will now be ready for use; be aware that the curing process can cause tiny cracks in the glaze and also some darkening with patina. This is completely normal and even desirable in some ways. Something else to keep in mind is that your tajine is most likely designed to be used in the oven only; I would not recommend using a terra cotta tajine - glazed or otherwise - on the stove-top, with the possible exception of cooking over low heat in conjunction with a heat diffuser. You can achieve perfectly delicious and even wonderful results by using your tajine in the oven, so it simply isn't worth the risk of cracking or shattering your tajine due to heat stress.

Enough talk - let's get to making this! Here's the recipe, from Time/Life's Foods of the World - a Quintet of Cuisines, 1970:

Tajine Msir Zitun

Chicken with Lemon and Olives

To serve 4:

4 tablespoons olive oil

A 3- to 3.5-pound chicken, cut into 8 serving pieces

1 cup finely chopped onions

2 teaspoons imported paprika

1 teaspoon ground ginger

1/4 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 salted lemons, cut into quarters, or substitute 2 fresh lemons, cut lengthwise into quarters and seeded

1 cup water

24 small green olives

In a heavy 12-inch skillet, warm the oil over high heat until a light haze forms above it. Brown the chicken in the hot oil, four pieces at a time, turning them frequently with tongs or a slotted spoon and regulating the heat so they color richly and evenly without burning. As they brown, transfer the chicken pieces to a plate.

Pour off all but a thin film of fat from the skillet and add the onions. Stirring frequently, cook for 8 to 10 minutes, until the onions are soft and brown. Watch carefully for any sign of burning and regulate the heat accordingly. Stir in the paprika, ginger, turmeric, salt and a few grindings of pepper. Add the fresh lemons (if you are using them), the chicken and the liquid that has accumulated around it, and pour in the water.

Bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce the heat to low and simmer covered for 30 minutes, or until the chicken is tender and shows no resistance when a thigh is pierced deeply with a small skewer or knife. Then add the olives and the salted lemon quarters (if you are using them), cover, and simmer for 4 or 5 minutes, until the lemons and olives are heated through. Taste for seasoning.

To serve, arrange the chicken pieces attractively on a deep platter and place the lemon quarters and olives in a ring around them. Pour the sauce over the chicken and serve at once.

Chicken with Lemon and Olives

To serve 4:

4 tablespoons olive oil

A 3- to 3.5-pound chicken, cut into 8 serving pieces

1 cup finely chopped onions

2 teaspoons imported paprika

1 teaspoon ground ginger

1/4 teaspoon turmeric

1 teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 salted lemons, cut into quarters, or substitute 2 fresh lemons, cut lengthwise into quarters and seeded

1 cup water

24 small green olives

In a heavy 12-inch skillet, warm the oil over high heat until a light haze forms above it. Brown the chicken in the hot oil, four pieces at a time, turning them frequently with tongs or a slotted spoon and regulating the heat so they color richly and evenly without burning. As they brown, transfer the chicken pieces to a plate.

Pour off all but a thin film of fat from the skillet and add the onions. Stirring frequently, cook for 8 to 10 minutes, until the onions are soft and brown. Watch carefully for any sign of burning and regulate the heat accordingly. Stir in the paprika, ginger, turmeric, salt and a few grindings of pepper. Add the fresh lemons (if you are using them), the chicken and the liquid that has accumulated around it, and pour in the water.

Bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce the heat to low and simmer covered for 30 minutes, or until the chicken is tender and shows no resistance when a thigh is pierced deeply with a small skewer or knife. Then add the olives and the salted lemon quarters (if you are using them), cover, and simmer for 4 or 5 minutes, until the lemons and olives are heated through. Taste for seasoning.

To serve, arrange the chicken pieces attractively on a deep platter and place the lemon quarters and olives in a ring around them. Pour the sauce over the chicken and serve at once.

I was pleasantly surprised at how easy this was to make, and how smoothly the preparation flowed. Cooking with a tajine is another one of those projects that I had been putting off, due to a perception that it would be complicated, intricate or otherwise difficult, and I was intimidated by the perceived challenge and risk of failure. In this case, as in so many others, I was proven completely wrong - it was easy! My advice, if you have any interest at all in trying this, is to put aside any concerns you might have and simply give it a go - you will be glad that you did!

Something be aware of is that this is truly a dish from antiquity. The "youngest" ingredient in the recipe is the paprika, which dates back to the 16th Century and is, by all definitions, ancient; but one should keep in mind that it would be just as easy to remove that component and go back over a thousand years with this dish. When you stop and think about that, things take on a whole level of significance; it's almost like time travel.

Here's a shot of the goods, as per the recipe:

As you can see, there's nothing there that really would be considered exotic or hard-to-get. The sole exception might be the smoked paprika, which I chose to use in lieu of the "regular" paprika specified in the recipe; in other words, use whatever paprika you wish, the higher-quality the better. If you are able to get your hands on some smoked paprika, however, you will be rewarded with a truly unique experience that, in my opinion, brings you much closer to a verdant oasis in the middle of the desert under a clear, starry sky and crescent moon. One convenient source for smoked paprika is the internet, where it can be found at places such as www.amazon.com or www.latienda.com, where it is marketed as pimentón de la vera.

If you look to the left in the photo, you will see a jar of msir, which is nothing more than lemons that have been "dried" by quartering and salting them, as Field discovered in Morocco:

At one point I had to ask our hostess to stop and tell me what she was doing. I had been intrigued from the start by whole lemons packed tightly in a jar. When she added the quartered lemons along with a handful of green olives to the browned chicken, she explained that the lemons - called msir - were a gift from her mother, who had pickled them in salt; they were indispensable, she said, to the making of this Moroccan tajine.... The lemons, I discovered at dinner, provided brilliant accents of acidity - a perfect foil for the chicken.

This tajine can be made without them, but I will say that these are, in my opinion, essential to the dish if one really wants to experience it, and there is no reason to go without them, especially since they are so easy to make. More on this in a moment....

But it looks to me as though something is missing - what could it be?

Ah, yes - the chicken!

For this preparation, I chose to use 9 boneless, skinless chicken thighs, which are full of flavour. The truth is, however, you can use any combination of chicken: a whole, cut up chicken, breasts, legs, bone-in, skin-on, Cornish game hens - whatever you prefer. For that matter, you can also use any number of various game birds such as dove, partridge, quail, squab, grouse, pheasant or chukar.

mise en place is pretty straightforward; simply dice your onion:

And measure your spices:

Clockwise from the top: smoked paprika, ginger, turmeric, salt and pepper.

Next, drain your olives and dump them into a bowl:

This is probably not necessary, but a lot can be said for being organised and ready, because things can and often do happen fast in the kitchen.

For some reason, I really went wild and combined jumbo black olives with smaller green olives, but no worries; you can use any olives you like, of any size you prefer. When using olives at the smaller end of the scale, however, you might want to double the amount.

The final piece of prep work involved the msir. As I said before, these are nothing more than lemons that have been naturally "dehydrated" by applying salt to them. Here is a link that gives an in-depth explanation and step-by-step pictures on how to do this:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/msir-moroccan-salted-dried-lemons_topic479.html

For those wanting a quick summary, you simply need to wash your lemons, cut their ends off, stand them up on end, quarter them "the long way" almost completely through, gently open them up like a flower, apply a little salt to the surfaces of the pulp inside, then close the "flower." Pack the lemons into a jar and place the jar somewhere where it can be undisturbed for at least two weeks while the salt works its magic; during that time, you might want to to rotate the jar periodically - in order to distribute the salt - and crack the lid open, in order to release built-up pressure. At the end of two weeks, and periodically after that, open the jar and pour off any accumulated juice. It won't take long until the effects of the salting will become evident; the lemons actually will "dry out," and will be able to be stored in the jar - with or without refrigeration - for a very long time, until ready for use. This preservation technique is essential in the hot, dry climate of the Maghreb, and it lends a great amount of authenticity to many varieties of tajines; however, if you do not have any msir on hand, and do not have time to make any, you can still make a perfectly acceptable tajine using fresh lemons. Probably any tajine recipe would respond well, but you should have especially good results using Brook's recipe here, which doesn't call for msir:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/lemon-chicken-tajine_topic1852.html

Anyway, proceeding forward, here is how to prepare the msir so that they will be ready to be used in this dish. Take two lemons' worth (8 quarters in all) and if they are not already separated, go ahead and do so. Next, run a good, sharp, thin-bladed knife such as a fillet knife between the pulp and the peel, thusly:

This will leave you with a segment that is composed primarily of peel:

Then, simply dice the segments into small pieces:

Leaving you with this:

This dicing step is not mentioned in the recipe; however, it made intuitive sense to do so at the time; one can leave the quarters whole, or cut them up for even distribution, as preference or whim dictates.

I tried one of the pieces and was amazed at the truly unique flavour that it had. It was had a fresh, acidic, intensely-lemony taste, with a slightly salty accent and just a suggestion of bitterness from the peel to balance everything out. Impressive, to be sure; as I said above, it really transports you to the Maghreb, and even though you can use fresh, "unpreserved" lemons, I strongly believe that your tajine experience is somewhat incomplete with msir.

Enough prep work - let's get to cooking this stuff!

A person could simply combine the ingredients in a tajine and cook it that way, resulting in a completely authentic tajine; however, I chose to go an extra step and do some pre-browning - which as far as I can tell is also practiced in North Africa - both for flavour and in order to get a head start on the cooking of the dish.

Keepng in mind that I would be adding more seasoning later, I very-lightly salted and peppered the chicken thighs, then seared them in batches in a little hot olive oil, using my cast iron Dutch oven:

In North Africa, this step would most likely be done in the tajine itself over a low flame; however, using an electric stove, I was concerned about cracking my tajine due to heat stress - not having a heat diffuser, I chose to use the cast iron.

Keep in mind that you do not want to cook the chicken all the way through; the goal is to get some browning on the outside of the chicken and warm it up a bit. Here, they are not quite browned enough:

So I turned them over a couple of times and continued to cook them until they took on a beautiful, golden sear.

In the picture above, note the fond that is developing on the bottom of the Dutch oven; this will become extremely wonderful, deep flavour later on as the chicken braises in the tajine.

Once all the pieces were nicely browned; I placed them in the tajine:

As I said before, a tajine is not absolutely, 100% necessary in order to make this dish; you can easily find and purchase a tajine on the internet, using online sources such as or, if you are close to a store such as World Market, you can get one there:

www.worldmarket.com

However, if you absolutely want to make this right now and don't have a tajine, a covered casserole, Dutch oven, slow cooker or baking dish will give acceptable results. If you choose to go this route, I would suggest consulting Chris's outstanding "Tajine sans Tajine" thread here:

foodsoftheworld.activeboards.net/tajine-sans-tajine-the-easy-diy-approach_topic2171.html

The methods that he outlines will be useful with this recipe, or probably any other that you would like to try, using non-traditional or modern cookware.

It is here that I did make one mistake in the preparation of this dish; the instructions state that the msir should be added toward the end, during the last 5 minutes or so of cooking; however, I forgot that little bit of advice, and added them here:

No real worries, as the dish seemed to turn out just fine, but it is something to be aware of as I am sure that the lemon was infused into the dish somewhat more than probably intended; this can be good - or not-so-good - depending on your outlook.

In any case, once the chicken is browned, things start moving forward fairly quickly. Carefully - so as not to disturb the wonderful, beautiful fond - drain off any excess oil, leaving a tablespoon or so. Then, bring up the heat a little and toss in the onions, stirring them around to pick up the fond while they caramelise:

When the onions just start to take on a golden-brown appearance at the edges, remove from the heat and toss in your spices, stirring to coat:

The reason for removing your cooking vessel from the heat is because many herbs and spices, particularly paprika, run the risk of scorching when added to direct heat; this will have many negative consequences, including but not limited to scorched flavour, grittiness and blackening. Having said that, many spices, particularly paprika, really come into their own when combined with heat and fat, releasing beautiful, deep colours and rich, wonderful aromas and flavours. It is a fine line to walk, but once you learn to navigate it, the food you cook will take on a whole new level of complex goodness.

Once the spices are worked into the fat and thoroughly incorporated into the onions, add the water:

Broth or stock could also be used, adding yet one more layer to the masterpiece that will become your dish; if you go with broth or stock, keep the salt content in mind during preparation.

Bring the mixture to a simmer, stirring frequently and taking care to lift any residual bits that might be stuck to the bottom of the pan, then pour all of this into the tajine on top of the chicken and msir:

The beauty of braising in general, and tajine cooking in particular, is that the steam from cooking will rise up, condense in the lid, and then run back down the inside of the lid in order to keep the food moist, tender and juicy. A little bit of liquid is all you need (in this case, a cup or a cup-and-a-half, at most), and the small amount of evaporation that does take place will serve to reduce the resulting juices down to a rich, flavourful sauce.

Next, run a thin scrim of olive oil around the rim of the tajine lid, in order to help with sealing, then place the tajine in a cold oven and turn it on to 325. Alternately, I suppose that simmering could take place on the stove-top, but as I said before, I was very reluctant to try this without a heat diffuser; besides, it seemed to me that an oven would be better for heating the dish from all sides.

While this concoction was simmering in the oven, a beautiful thing began to happen; the entire house was slowly filled with warm, wonderful aromas as the spices intermingled with the chicken, onion, msir and other components of the dish. It was all one could do to not lift the lid and take a peek - but such self-discipline is one of the things that separates us from the animals, so we resisted the urge.

Since I was cooking at a tajine-safe temperature that was lower than the one in the recipe, I added 15 or 20 minutes to the total proscribed cooking time. After an hour or so, we removed the tajine from the oven, checked the chicken for doneness and added the olives:

It was here that I realised this is where I should have added the misr, according to the recipe, but no worries; also, as mentioned above, the vast difference in the sizes of the olives was a bit awkward, but in the end they tasted great, and that's what mattered.

I returned the tajine to the oven for another 5 or 10 minutes, and then removed the dish from the oven and took a look at what I had created:

Well, I would call that a success, especially for a first time - and so easy - I really can't get across to you just how easy this was; you're just going to have to try it for yourself and see!

The traditional accompaniment for most tajines is couscous. I had been wondering about the best way to go about this, when I noticed the still-bubbling cooking liquid in the tajine:

This sight resulted in a flash of inspiration, and I quickly acted on it. First, I removed the chicken pieces to a covered dish in order to keep warm; then, I dumped a box of couscous into the tajine,gave it a quick, gentle stir to distribute it, and returned the lid so that the pasta could absorb the cooking liquids - along with all of the wonderful flavours therein. Couscous takes only a few moments to cook, due to the very small size of its grains, and it seemed to me that this method must be so obvious as to be consistent with methods in North Africa. Some sources mention steaming the couscous above the food as it cooks, but this improvisation seemed practical and easy, achieving the same results, so I did it this way. My only concern was whether there would be enough liquid to fully reconstitute the pasta, so I added jsut a little more boiling water to the tajine and waited another minute or three, and it seemed to work very well, soaking up the excess liquid and leaving behind a wonderful sauce. A small test-sampling of the couscous revealed that it was cooked perfectly and full of rich, lively bits of flavor from the onion and msir, brought together by the savory chicken broth, earthy spices and other components in the cooking liquid - but there was indeed something more than this - just a little extra goodness that I would attribute to the magic of the Maghreb!

I served this seemingly humble, yet majestic dish with a simple salad of vinegar-soaked cucumbers topped with tzatziki:

By now, after going through the preparation steps for it, smelling it during cooking, a quick look when I added the olives and that tantalizing, oh-too-brief sample of couscous to see if it was ready, my mouth was watering and I was ready to experience this dish - and I wasn't disappointed at all. I knew that it was going to be good, bordering on fantastic, but I was unprepared for the absolute symphony that erupted in my mouth, bringing together savory depth, earthy warmth, citrusy accents and so many other things to the party. It was easily one of the most impressive dishes I have made, which is surprising, considering the relatively humble nature of the ingredients, when considered individually. It was still amazing to me that this rich, complex, exotic-tasting dish could be so incredibly easy to prepare; and yet, the proof of this was bringing my taste buds to their knees with pleasure.

The rest of the family enjoyed it in general, but the beautiful Mrs. Tas, while indeed liking the meal over-all, didn't care for the mouth feel of the couscous, with its smaller-than-rice grains of pasta, and wasn't impressed with the lemon aspect. As for myself, I was thoroughly impressed with the whole thing, especially the way the flavours married in the tajine in order to produce something that was so much more than the sum of their individual roles. I'll definitely be doing this and other tajine dishes in the future.

This was once again an example of how some guy in Montana - pretty much a novice at cooking and completely unfamiliar with the mystique of the Maghreb, was able to take himself and his family on a journey through time and space, with the help and encouragement of the friends he had made and the experiences they had had. We were once again transported across the sea - this time to that aforementioned, lush oasis in North Africa under the crescent moon of a star-filled sky. It could have been that this very same dish was served in a Moroccan household the night before, or even hundreds of years ago, when oriental spices - and their trade - created and destroyed empires.

My sincere thanks to Dave, Margi, Brook, Ahron, Chris, John, and others who not only opened the door for me, but also gave me the kick in the rear to go through it. When we study, create and share experiences such as this, we truly are preserving that distant past, so that the distant future might perhaps remember and benefit from it. I do hope that you are inspired to give this a try, and that I have drawn a clear map for your journey; however, if you have any questions, just ask, and they shall be answered.

I have a tagine that I make with chicken, olives, raisins (supposed to be dates, but you use what you have) and almonds. YUM. ;D This one looks pretty good, too, although I haven't had time to read your entire post. I'll have to put it on my list to try. I have to make mine in a big cast iron frying pan, though.

I have a tagine that I make with chicken, olives, raisins (supposed to be dates, but you use what you have) and almonds. YUM. ;D This one looks pretty good, too, although I haven't had time to read your entire post. I'll have to put it on my list to try. I have to make mine in a big cast iron frying pan, though.